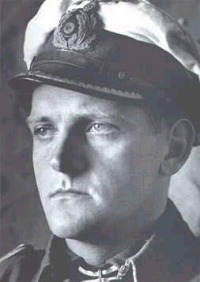

By: Erich Topp

Date: 1999-11-08

Erich Topp joined the German U-Boat arm in October 1937 (Crew 34), and a year later was appointed as a watch officer on U-46 (Kptlt. Herbert Sohler). After four patrols, Topp was given command of U-57, a Type II boat, with which he sank six ships totaling 37,000 tons.

After 17 combat war patrols, Topp was reassigned as commander of the 27th U-Boat Flotilla. In that capacity he trained new crews and in 1944 drafted the tactical battle instructions for the Type XXI Electro boats.

After the war, Topp worked as a common fisherman and eventually became a successful architect. He joined the West German Navy in 1958 and served in several high-ranking staff positions with NATO.

Topp retired as a Konteradmiral in December 1969. Thereafter, he served as an industrial consultant for many years and penned his autobiography, The Odyssey of a U-Boat Commander: The Recollections of Erich Topp (Praeger, 1992). Admiral Topp lives today in Remagen, Germany and is a consultant on SSI's coming Silent Hunter II and Destroyer Command.

The Wolf Pack

Admiral Donitz developed this system as a means of stopping the shipment of supplies across the Atlantic Ocean. In the beginning of the war, our secret service was able to decode the enemy messages given to the convoys. This enabled us to locate our submarines in a line confronting the expected course of the convoy.

A distance of about 50 km was to be kept between each boat, although in practice this was not always possible. This enabled our boats to either find the convoy visually or with our listening devices, which would pick up their propeller noises. The idea was that the first boat to establish contact with the convoy would radio headquarters and other boats in the line (or group) and alert them to the presence of the convoy.

All the boats were then to proceed as fast as possible (maximum surface speed was about 18 knots) to establish visual contact with the convoy and await instructions. The average speed of a typical Atlantic convoy was about 8-9 knots, a speed dependent on the slowest ship in the convoy.

If our submarines established visual contact during daylight hours, we were instructed to obtain a position ahead of the convoy, dive, and conduct an attack at periscope depth. Convoys were usually protected by destroyers and corvettes escorts, which were typically posted 2,000 - 3,000 meters outside the convoy, forming a protective ring around the ships. Our goal was to penetrate this protective line and to attack the ships from as close as possible, and then withdraw to reload our torpedoes, and then attack once again.

Allied advances in the field of electronics changed Wolf Pack tactics considerably. The introduction of the ship-borne High-Frequency-Direction-Finder, known as "Huff-Duff," fitted in increasing numbers of ships from the end of 1942 onward, enabled convoy escorts to take accurate bearings up to 25 km on U-boats, which transmitted near convoys.

The effectiveness of this was much enhanced by the German practice of abandoning radio silence, once contact was established with a convoy. This resulted in the loss of many boats and crews, who did not realize they were announcing their location to the enemy.

Another major development was radar. In darkness or in fog, the ship-borne radar on board of the Allied escorts (and airplanes) robbed the U-boats of their prime advantage: invisibility. These two factors, with advances in defensive and offensive escort tactics, better depth-charges, and the reading of transmissions because of the breaking of Enigma, made the Wolf Pack tactic obsolete.

Although we suspected certain advancements, we had no knowledge of the electronic advances on the Allied side. We did not know anything of the Huff-Duff system or Enigma until after the end of the war. Once U-boats lost their invisibility, their technical and tactical limitations became obvious. The Wolf Pack tactic had lost its effectiveness.

While on the surface, even when facing single escorts, a U-boat's self defense capabilities were very low. When forced to submerge, the chances of escaping a persistent hunt by an experienced team of warships--and the convoy escorts became more experienced as the war progressed -- were limited by the low underwater speed and endurance.

MY EXPERIENCES

During the pre-war years and the first two years of the war, U-boats conducted two-week tactical training excercises in the Baltic Sea. These exhausting exercises consisted of simulated attacks on convoys, formed of eight or more ships protected by escorts and airplanes. I engaged in these both as a commander of a U-boat, and later in the war as a Flotilla commander.

When attacking convoys early in the war, I always tried to pass the escorts and, if possible, attack from between the lines of the merchant ships. I had to keep in mind that I could not launch an attack from a distance less than 300 meters. Otherwise, we risked blowing ourselves up with our own torpedos.

Between the lines of the convoy I had some freedom to maneuver, because the merchant ships were bound to a certain order that did not allow them--even if they saw my U-boat--to change their course considerably, even to ram me.

The advances in Allied technology were evident when I attacked a convoy in 1942 on its way from Gibraltar to England. This convoy was under the command of the famous convoy-leader John Walker. The Wolf Pack system failed.

Of the several U-boats that tried to attack this convoy, only my boat was able to attack during the night at a distance of 3,000 meters. The other boats were prevented from approaching close enough or were sunk. Huff-Duff, radar, and advanced tactics defeated our best efforts.

For more on Uboats see Type VII to VIIC. See also Naval Combat Previews.